Excerpts from an Oral History Interview with Steve Jobs / Smithsonian Institution

Interviewer: Daniel Morrow, Executive Director, The Computerworld Smithsonian Awards Program

Date of Interview: 20 April 1995

Location: NeXT Computer

Transcript Editor: Thomas J. Campanella, Computerworld Smithsonian Awards

DM: What were the early things you were passionate about, that you were interested in?

SJ: I was very lucky. My father, Paul, was a pretty remarkable man. He never graduated from high school. He joined the coast guard in World War II and ferried troops around the world for General Patton; and I think he was always getting into trouble and getting busted down to Private. He was a machinist by trade and worked very hard and was kind of a genius with his hands. He had a workbench out in his garage where, when I was about five or six, he sectioned off a little piece of it and said "Steve, this is your workbench now." And he gave me some of his smaller tools and showed me how to use a hammer and saw and how to build things. It really was very good for me. He spent a lot of time with me . . . teaching me how to build things, how to take things apart, put things back together.

One of the things that he touched upon was electronics. He did not have a deep understanding of electronics himself but he'd encountered electronics a lot in automobiles and other things he would fix. He showed me the rudiments of electronics and I got very interested in that. I grew up in Silicon Valley. My parents moved from San Francisco to Mountain View when I was five. My dad got transferred and that was right in the heart of Silicon Valley so there were engineers all around. Silicon Valley for the most part at that time was still orchards--apricot orchards and prune orchards--and it was really paradise. I remember the air being crystal clear, where you could see from one end of the valley to the other.

DM: This was when you were six, seven, eight years old at the time.

SJ: Right. Exactly. It was really the most wonderful place in the world to grow up. There was a man who moved in down the street, maybe about six or seven houses down the block who was new in the neighborhood with his wife, and it turned out that he was an engineer at Hewlett-Packard and a ham radio operator and really into electronics. What he did to get to know the kids in the block was rather a strange thing: he put out a carbon microphone and a battery and a speaker on his driveway where you could talk into the microphone and your voice would be amplified by the speaker. Kind of strange thing when you move into a neighborhood but that's what he did.

DM: This is great.

SJ: I of course started messing around with this. I was always taught that you needed an amplifier to amplify the voice in a microphone for it to come out in a speaker. My father taught me that. I proudly went home to my father and announced that he was all wrong and that this man up the block was amplifying voice with just a battery. My father told me that I didn't know what I was talking about and we got into a very large argument. So I dragged him down and showed him this and he himself was a little befuddled.

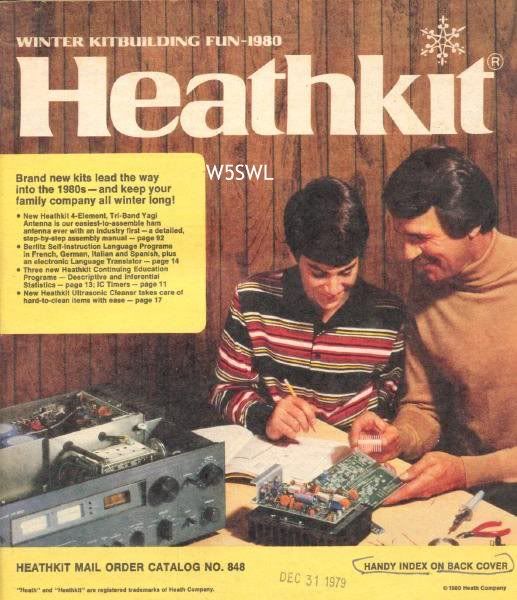

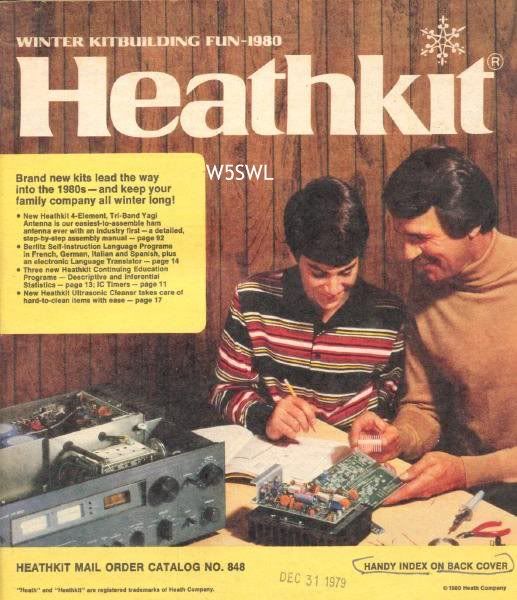

I got to know this man, whose name was Larry Lang, and he taught me a lot of electronics. He was great. He used to build Heathkits. Heathkits were really great. Heathkits were these products that you would buy in kit form. You actually paid more money for them than if you just went and bought the finished product if it was available. These Heathkits would come with these detailed manuals about how to put this thing together and all the parts would be laid out in a certain way and color coded. You'd actually build this thing yourself. I would say that this gave one several things. It gave one a understanding of what was inside a finished product and how it worked because it would include a theory of operation but maybe even more importantly it gave one the sense that one could build the things that one saw around oneself in the universe. These things were not mysteries anymore. I mean you looked at a television set you would think that "I haven't built one of those but I could. There's one of those in the Heathkit catalog and I've built two other Heathkits so I could build that." Things became much more clear that they were the results of human creation not these magical things that just appeared in one's environment that one had no knowledge of their interiors. It gave a tremendous level of self-confidence, that through exploration and learning one could understand seemingly very complex things in one's environment. My childhood was very fortunate in that way.

DM: It sounds like you were really lucky to have your dad as sort of a mentor. I was going to ask you about school. What was the formal side of your education like? Good? Bad?

SJ: School was pretty hard for me at the beginning. My mother taught me how to read before I got to school and so when I got there I really just wanted to do two things. I wanted to read books because I loved reading books and I wanted to go outside and chase butterflies. You know, do the things that five year olds like to do. I encountered authority of a different kind than I had ever encountered before, and I did not like it. And they really almost got me. They came close to really beating any curiosity out of me. By the time I was in third grade, I had a good buddy of mine, Rick Farentino, and the only way we had fun was to create mischief. I remember we traded everybody. There was a big bike rack where everybody put their bikes, maybe a hundred bikes in this rack, and we traded everybody our lock combinations for theirs on an individual basis and then went out one day and put everybody's lock on everybody else's bike and it took them until about ten o'clock that night to get all the bikes sorted out. We set off explosives in teacher's desks. We got kicked out of school a lot. In fourth grade I encountered one of the other saints of my life. They were going to put Rick Farentino and I into the same fourth grade class, and the principal said at the last minute "No, bad idea. Separate them." So this teacher, Mrs. Hill, said "I'll take one of them." She taught the advanced fourth grade class and thank God I was the random one that got put in the class. She watched me for about two weeks and then approached me. She said "Steven, I'll tell you what. I'll make you a deal. I have this math workbook and if you take it home and finish on your own without any help and you bring it back to me, if you get it 80% right, I will give you five dollars and one of these really big suckers she bought and she held it out in front of me. One of these giant things. And I looked at her like "Are you crazy lady"? Nobody's ever done this before and of course I did it. She basically bribed me back into learning with candy and money and what was really remarkable was before very long I had such a respect for her that it sort of re-ignited my desire to learn. She got me kits for making cameras. I ground my own lens and made a camera. It was really quite wonderful. I think I probably learned more academically in that one year than I learned in my life. It created problems though because when I got out of fourth grade they tested me and they decided to put me in high school and my parents said "No.". Thank God. They said "He can skip one grade but that's all."

DM: But not to high school.

SJ: And I found skipping one grade to be very troublesome in many ways. That was plenty enough. It did create some problems.

The Importance of Education

SJ: I'm sure it did. I'm a very big believer in equal opportunity as opposed to equal outcome. I don't believe in equal outcome because unfortunately life's not like that. It would be a pretty boring place if it was. But I really believe in equal opportunity. Equal opportunity to me more than anything means a great education. Maybe even more important than a great family life, but I don't know how to do that. Nobody knows how to do that. But it pains me because we do know how to provide a great education. We really do. We could make sure that every young child in this country got a great education. We fall far short of that. I know from my own education that if I hadn't encountered two or three individuals that spent extra time with me, I'm sure I would have been in jail. I'm 100% sure that if it hadn't been for Mrs. Hill in fourth grade and a few others, I would have absolutely have ended up in jail. I could see those tendencies in myself to have a certain energy to do something. It could have been directed at doing something interesting that other people thought was a good idea or doing something interesting that maybe other people didn't like so much. When you're young, a little bit of course correction goes a long way. I think it takes pretty talented people to do that. I don't know that enough of them get attracted to go into public education. You can't even support a family on what you get paid. I'd like the people teaching my kids to be good enough that they could get a job at the company I work for, making a hundred thousand dollars a year. Why should they work at a school for thirty-five to forty thousand dollars if they could get a job here at a hundred thousand dollars a year? Is that an intelligence test? The problem there of course is the unions. The unions are the worst thing that ever happened to education because it's not a meritocracy. It turns into a bureaucracy, which is exactly what has happened. The teachers can't teach and administrators run the place and nobody can be fired. It's terrible.

DM: Some people say that this new technology maybe a way to bypass that. Are you optimistic about that?

The Role of Computers in Education

SJ: I absolutely don't believe that. As you've pointed out I've helped with more computers in more schools than anybody else in the world and I absolutely convinced that is by no means the most important thing. The most important thing is a person. A person who incites your curiosity and feeds your curiosity; and machines cannot do that in the same way that people can. The elements of discovery are all around you. You don't need a computer. Here - why does that fall? You know why? Nobody in the entire world knows why that falls. We can describe it pretty accurately but no one knows why. I don't need a computer to get a kid interested in that, to spend a week playing with gravity and trying to understand that and come up with reasons why.

DM: But you do need a person.

SJ: You need a person. Especially with computers the way they are now. Computers are very reactive but they're not proactive; they are not agents, if you will. They are very reactive. What children need is something more proactive. They need a guide. They don't need an assistant. I think we have all the material in the world to solve this problem; it's just being deployed in other places. I've been a very strong believer in that what we need to do in education is to go to the full voucher system. I know this isn't what the interview was supposed to be about but it is what I care about a great deal.

Interviewer: Daniel Morrow, Executive Director, The Computerworld Smithsonian Awards Program

Date of Interview: 20 April 1995

Location: NeXT Computer

Transcript Editor: Thomas J. Campanella, Computerworld Smithsonian Awards

DM: What were the early things you were passionate about, that you were interested in?

SJ: I was very lucky. My father, Paul, was a pretty remarkable man. He never graduated from high school. He joined the coast guard in World War II and ferried troops around the world for General Patton; and I think he was always getting into trouble and getting busted down to Private. He was a machinist by trade and worked very hard and was kind of a genius with his hands. He had a workbench out in his garage where, when I was about five or six, he sectioned off a little piece of it and said "Steve, this is your workbench now." And he gave me some of his smaller tools and showed me how to use a hammer and saw and how to build things. It really was very good for me. He spent a lot of time with me . . . teaching me how to build things, how to take things apart, put things back together.

One of the things that he touched upon was electronics. He did not have a deep understanding of electronics himself but he'd encountered electronics a lot in automobiles and other things he would fix. He showed me the rudiments of electronics and I got very interested in that. I grew up in Silicon Valley. My parents moved from San Francisco to Mountain View when I was five. My dad got transferred and that was right in the heart of Silicon Valley so there were engineers all around. Silicon Valley for the most part at that time was still orchards--apricot orchards and prune orchards--and it was really paradise. I remember the air being crystal clear, where you could see from one end of the valley to the other.

DM: This was when you were six, seven, eight years old at the time.

SJ: Right. Exactly. It was really the most wonderful place in the world to grow up. There was a man who moved in down the street, maybe about six or seven houses down the block who was new in the neighborhood with his wife, and it turned out that he was an engineer at Hewlett-Packard and a ham radio operator and really into electronics. What he did to get to know the kids in the block was rather a strange thing: he put out a carbon microphone and a battery and a speaker on his driveway where you could talk into the microphone and your voice would be amplified by the speaker. Kind of strange thing when you move into a neighborhood but that's what he did.

DM: This is great.

SJ: I of course started messing around with this. I was always taught that you needed an amplifier to amplify the voice in a microphone for it to come out in a speaker. My father taught me that. I proudly went home to my father and announced that he was all wrong and that this man up the block was amplifying voice with just a battery. My father told me that I didn't know what I was talking about and we got into a very large argument. So I dragged him down and showed him this and he himself was a little befuddled.

I got to know this man, whose name was Larry Lang, and he taught me a lot of electronics. He was great. He used to build Heathkits. Heathkits were really great. Heathkits were these products that you would buy in kit form. You actually paid more money for them than if you just went and bought the finished product if it was available. These Heathkits would come with these detailed manuals about how to put this thing together and all the parts would be laid out in a certain way and color coded. You'd actually build this thing yourself. I would say that this gave one several things. It gave one a understanding of what was inside a finished product and how it worked because it would include a theory of operation but maybe even more importantly it gave one the sense that one could build the things that one saw around oneself in the universe. These things were not mysteries anymore. I mean you looked at a television set you would think that "I haven't built one of those but I could. There's one of those in the Heathkit catalog and I've built two other Heathkits so I could build that." Things became much more clear that they were the results of human creation not these magical things that just appeared in one's environment that one had no knowledge of their interiors. It gave a tremendous level of self-confidence, that through exploration and learning one could understand seemingly very complex things in one's environment. My childhood was very fortunate in that way.

DM: It sounds like you were really lucky to have your dad as sort of a mentor. I was going to ask you about school. What was the formal side of your education like? Good? Bad?

SJ: School was pretty hard for me at the beginning. My mother taught me how to read before I got to school and so when I got there I really just wanted to do two things. I wanted to read books because I loved reading books and I wanted to go outside and chase butterflies. You know, do the things that five year olds like to do. I encountered authority of a different kind than I had ever encountered before, and I did not like it. And they really almost got me. They came close to really beating any curiosity out of me. By the time I was in third grade, I had a good buddy of mine, Rick Farentino, and the only way we had fun was to create mischief. I remember we traded everybody. There was a big bike rack where everybody put their bikes, maybe a hundred bikes in this rack, and we traded everybody our lock combinations for theirs on an individual basis and then went out one day and put everybody's lock on everybody else's bike and it took them until about ten o'clock that night to get all the bikes sorted out. We set off explosives in teacher's desks. We got kicked out of school a lot. In fourth grade I encountered one of the other saints of my life. They were going to put Rick Farentino and I into the same fourth grade class, and the principal said at the last minute "No, bad idea. Separate them." So this teacher, Mrs. Hill, said "I'll take one of them." She taught the advanced fourth grade class and thank God I was the random one that got put in the class. She watched me for about two weeks and then approached me. She said "Steven, I'll tell you what. I'll make you a deal. I have this math workbook and if you take it home and finish on your own without any help and you bring it back to me, if you get it 80% right, I will give you five dollars and one of these really big suckers she bought and she held it out in front of me. One of these giant things. And I looked at her like "Are you crazy lady"? Nobody's ever done this before and of course I did it. She basically bribed me back into learning with candy and money and what was really remarkable was before very long I had such a respect for her that it sort of re-ignited my desire to learn. She got me kits for making cameras. I ground my own lens and made a camera. It was really quite wonderful. I think I probably learned more academically in that one year than I learned in my life. It created problems though because when I got out of fourth grade they tested me and they decided to put me in high school and my parents said "No.". Thank God. They said "He can skip one grade but that's all."

DM: But not to high school.

SJ: And I found skipping one grade to be very troublesome in many ways. That was plenty enough. It did create some problems.

The Importance of Education

SJ: I'm sure it did. I'm a very big believer in equal opportunity as opposed to equal outcome. I don't believe in equal outcome because unfortunately life's not like that. It would be a pretty boring place if it was. But I really believe in equal opportunity. Equal opportunity to me more than anything means a great education. Maybe even more important than a great family life, but I don't know how to do that. Nobody knows how to do that. But it pains me because we do know how to provide a great education. We really do. We could make sure that every young child in this country got a great education. We fall far short of that. I know from my own education that if I hadn't encountered two or three individuals that spent extra time with me, I'm sure I would have been in jail. I'm 100% sure that if it hadn't been for Mrs. Hill in fourth grade and a few others, I would have absolutely have ended up in jail. I could see those tendencies in myself to have a certain energy to do something. It could have been directed at doing something interesting that other people thought was a good idea or doing something interesting that maybe other people didn't like so much. When you're young, a little bit of course correction goes a long way. I think it takes pretty talented people to do that. I don't know that enough of them get attracted to go into public education. You can't even support a family on what you get paid. I'd like the people teaching my kids to be good enough that they could get a job at the company I work for, making a hundred thousand dollars a year. Why should they work at a school for thirty-five to forty thousand dollars if they could get a job here at a hundred thousand dollars a year? Is that an intelligence test? The problem there of course is the unions. The unions are the worst thing that ever happened to education because it's not a meritocracy. It turns into a bureaucracy, which is exactly what has happened. The teachers can't teach and administrators run the place and nobody can be fired. It's terrible.

DM: Some people say that this new technology maybe a way to bypass that. Are you optimistic about that?

The Role of Computers in Education

SJ: I absolutely don't believe that. As you've pointed out I've helped with more computers in more schools than anybody else in the world and I absolutely convinced that is by no means the most important thing. The most important thing is a person. A person who incites your curiosity and feeds your curiosity; and machines cannot do that in the same way that people can. The elements of discovery are all around you. You don't need a computer. Here - why does that fall? You know why? Nobody in the entire world knows why that falls. We can describe it pretty accurately but no one knows why. I don't need a computer to get a kid interested in that, to spend a week playing with gravity and trying to understand that and come up with reasons why.

DM: But you do need a person.

SJ: You need a person. Especially with computers the way they are now. Computers are very reactive but they're not proactive; they are not agents, if you will. They are very reactive. What children need is something more proactive. They need a guide. They don't need an assistant. I think we have all the material in the world to solve this problem; it's just being deployed in other places. I've been a very strong believer in that what we need to do in education is to go to the full voucher system. I know this isn't what the interview was supposed to be about but it is what I care about a great deal.